3. Deciding on important outcomes

3.1. General approach

Outcomes may include survival (mortality), clinical events (e.g. stroke or myocardial infarction), patient-reported outcomes (e.g. specific symptoms, quality of life), adverse events, burdens (e.g. demands on caregivers, frequency of tests, restrictions on lifestyle) and economic outcomes (e.g. cost and resource use). It is critical to identify both outcomes related to adverse effects/harm as well as outcomes related to effectiveness.

Review authors should consider how outcomes should be measured, both in terms of the type of scale likely to be used and the timing of measurement. Outcomes may be measured objectively (e.g. blood pressure, number of strokes) or subjectively as rated by a clinician, patient or carer (e.g. disability scales). It may be important to specify whether measurement scales have been published or validated.

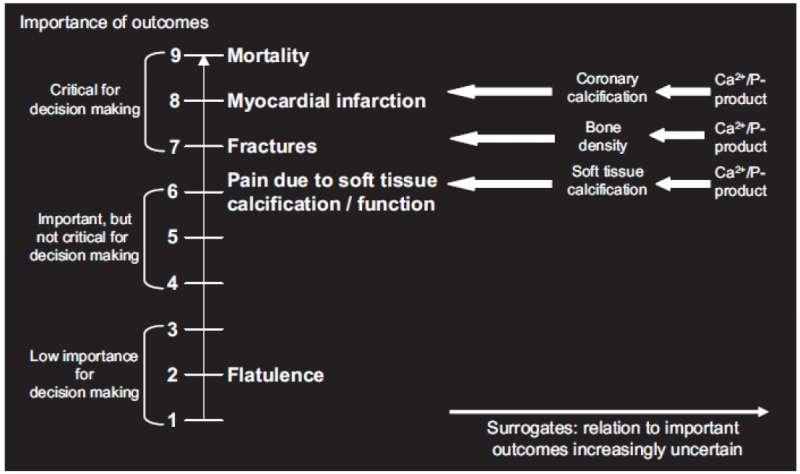

GRADE specifies three categories of outcomes according to their importance. Guideline developers must, and authors of systematic reviews are strongly encouraged to specify all potential patient-important outcomes as the first step in their endeavour. The guideline development group should classify outcomes as:

- Critical;

- Important, but not critical;

- Of limited importance.

The first two classes of outcomes will bear on guideline recommendations; the third may or may not. Ranking outcomes by their relative importance can help to focus attention on those outcomes that are considered most important, and help to resolve or clarify disagreements. GRADE recommends to focus on a maximum of 7 critical and/or important outcomes.

Guideline developers should first consider whether particular desirable or undesirable consequences of a therapy are important to the decision regarding the optimal management strategy, or whether they are of limited importance. If the guideline panel thinks that a particular outcome is important, then it should consider whether the outcome is critical to the decision, or only important, but not critical. To facilitate ranking of outcomes according to their importance guideline developers as well as authors of systematic reviews may choose to rate outcomes numerically on a 1 to 9 scale (7 to 9 – critical; 4 to 6 – important; 1 to 3 – of limited importance) to distinguish between importance categories.

For each recommendations GRADE proposes to limit the number of outcomes to a maximum of 7.

3.2. Perspective of outcomes

Different audiences are likely to have different perspectives on the importance of outcomes.

The importance of outcomes is likely to vary within and across cultures or when considered from the perspective of patients, clinicians or policy-makers. It is essential to take cultural diversity into account when deciding on relative importance of outcomes, particularly when developing recommendations for an international audience. Guideline panels should also decide what perspective they are taking. Guideline panels may also choose to take the perspective of the society as a whole (e.g. a guideline panel developing recommendations about pharmacological management of bacterial sinusitis may take the patient perspective when considering health outcomes, but also a society perspective when considering antimicrobial resistance to specific drugs).

3.3. Before and after literature review

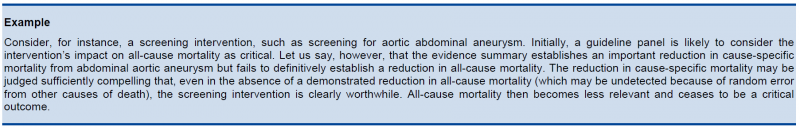

For a guideline, an initial rating of the importance of outcomes should precede the review of the evidence, and this rating should be confirmed or revised following the evidence review.

One should aim to decide which outcomes are important during protocol development and before one undertakes a systematic review or guideline project.

However, rating importance of an outcome prior to evidence review is preliminary: when evidence becomes available a reassessment of importance is necessary.

Guideline panels should be aware that in some instances the importance of an outcome may only become known after the protocol is written, evidence is reviewed or the analyses are carried out, and should take appropriate actions to include these in the evidence tables.

Outcomes that are critical to decision making should be included in an evidence table whether or not information about them is available.

3.4. Implications of the classification

Only outcomes considered critical (rated 7—9) or important (rated 4—6) should be included in the evidence profile.

Only outcomes considered critical (rated 7—9) are the primary factors influencing a recommendation and should be used to determine the overall quality of evidence supporting this recommendation.

When determining which outcomes are critical, it is important to bear in mind that absence of evidence on a critical outcome automatically leads to a downgrading of the evidence.

3.5. Expert involvement

Experts and stakeholders should be involved when determining the research questions and important outcomes. At KCE this usually consists of inviting a number of experts in the field to an expert meeting. While interactions between experts often are useful, there is a real danger that unprepared meetings lead to ‘suboptimal’ decisions. The following may make this process easier:

- Try to make them focus on the really important questions, there are usually lots of interesting questions but scope needs to be limited

- Explain on forehand the implications of the term ‘critical outcome’. It is useful to ask the question on beforehand: is the outcome that critical that one is prepared to downgrade the level of evidence if insufficient evidence is found for this particular outcome.

- Make a proposal on beforehand, expert meetings are often too short to construct a complete framework of questions with the relevant outcomes from scratch by the invited experts.

- It may be useful to ask experts on beforehand to provide ratings for the different outcomes (e.g. in an Excel sheet) and ask them to put their justification in writing.

- Try to give an introduction on GRADE so that everybody has an understanding of what it is and what the implications are.

3.6. Use of surrogates

Guideline developers should consider surrogate outcomes only when high-quality evidence regarding important outcomes is lacking. When such evidence is lacking, guideline developers may be tempted to list the surrogates as their measures of outcome. This is not the approach GRADE recommends. Rather, they should specify the important outcomes and the associated surrogates they must use as substitutes. The necessity to substitute with the surrogate may ultimately lead to rating down the quality of the evidence because of indirectness.

3.7. Clinical decision threshold and minimally important difference

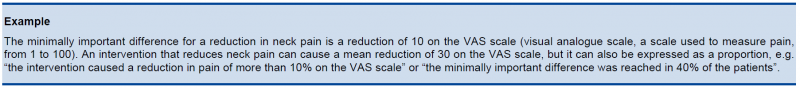

When important decisions are made about outcomes, it is also important to consider the minimal clinical importance of an effect size, as this is best decided before the evidence is collected and summarized, in order to avoid subjective and ad hoc decisions influenced by the available evidence.

GRADE uses the term Clinical Decision Threshold, i.e. the threshold that would change the decision whether or not to adopt a clinical action.

For binary outcomes this usually implies a risk reduction. The threshold is likely to differ according to the outcome, e.g. a mortality reduction of 10 % will be more important than a reduction of 10% in the number of patients developing a rash. For continuous outcomes, the minimally important difference is used, i.e. the smallest difference in outcome of interest that informed patients or proxies perceive to be important, either beneficial or harmful, and that would lead the patient or clinician to consider a change in management.

Notes

- A minimally important difference is measured at the individual level.

- The effect on a continuous outcome can be expressed as a mean difference, but also as the proportion of patients having a benefit that is above the minimally important difference.

Determining this threshold is not straightforward and often difficult. Expert opinion is often essential.

For a few outcomes validated thresholds exist based on evidence from surveys amongst patients, e.g. the Cochrane back pain group determined a threshold for back and neck pain. Doing a specific literature search on this topic is probably too labour-intensive and moreover, there are no universally accepted and agreed validated methods for doing so. Some rules of thumb are provided by the GRADE working group, such as an increase/decrease of 25%, but one should be cautious to apply these without a critical reflection on the context.

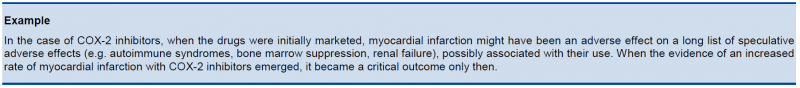

3.8. Adverse effects

Any intervention may be associated with adverse effects that are not initially apparent. Thus, one might consider ‘‘as-yet-undiscovered toxicity’’ as an important adverse consequence of any new drug. Such toxicity becomes critical only when sufficient evidence of its existence emerges.

The tricky part of this judgment is how frequently the adverse event must occur and how plausible the association with the intervention must be before it becomes a critical outcome. For instance, an observational study found a previously unsuspected association between sulfonylurea use and cancer-related mortality. Should cancer deaths now be an important, or even a critical, endpoint when considering sulfonylurea use in patients with type 2 diabetes? As is repeatedly the case, we cannot offer hard and fast rules for these judgments.