5.1. Introduction

GRADE specifies four quality categories (high, moderate, low, and very low) that are applied to a body of evidence, but not to individual studies. In the context of a systematic review, quality reflects our confidence that the effect estimates are correct. In the context of recommendations, quality reflects our confidence that the effect estimates are adequate to support a particular recommendation.

Guideline panels have to determine the overall quality of evidence across all the critical outcomes essential to a recommendation they make. Guideline panels usually provide a single grade of quality of evidence for every recommendation, but the strength of a recommendation usually depends on evidence regarding not just one, but a number of patient-important outcomes and on the quality of evidence for each of these outcomes.

When determining the overall quality of evidence across outcomes:

- Consider only those outcomes that are deemed critical;

- If the quality of evidence differs across critical outcomes and outcomes point in different directions — towards benefit and towards harm — the lowest quality of evidence for any of the critical outcomes determines the overall quality of evidence;

- If all outcomes point in the same direction — towards either benefit or harm — the highest quality of evidence for a critical outcome, that by itself would suffice to recommend an intervention, determines the overall quality of evidence. However, if the balance of the benefits and harms is uncertain, the grade of the critical outcome with the lowest quality grading should be assigned.

5.1.1. Four levels of evidence

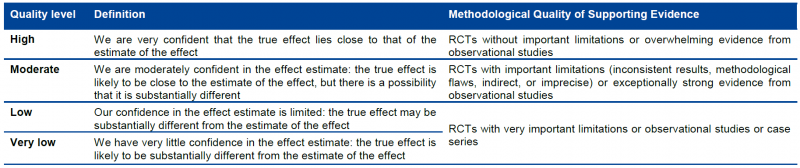

Randomized trials start as high-quality evidence, observational studies as low quality (see table). ‘‘Quality’’ as used in GRADE means more than risk of bias and may also be compromised by imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness of study results, and publication bias. In addition, several factors can increase our confidence in an estimate of effect. This general approach is summarized in the table below.

In the following chapters these factors will be discussed in depth. However, it is important to emphasize again that GRADE warns against applying this upgrading and downgrading in a too mechanistic way and to leave room for judgment.

Although GRADE suggests the initial separate consideration of five categories for rating down the quality of evidence and three categories for rating up, with a yes/no decision in each case, the final rating of overall evidence quality occurs in a continuum of confidence in the validity, precision, consistency, and applicability of the estimates. Fundamentally, the assessment of evidence quality remains a subjective process, and GRADE should not be seen as obviating the need for or minimizing the importance of judgment. As repeatedly stressed, the use of GRADE will not guarantee consistency in assessment, whether it is of the quality of evidence or of the strength of recommendation. There will be cases in which competent reviewers will have honest and legitimate disagreement about the interpretation of evidence. In such cases, the merit of GRADE is that it provides a framework that guides one through the critical components of this assessment and an approach to analysis and communication that encourages transparency and an explicit accounting of the judgments involved.

5.1.2. Overall quality of evidence

Guideline panels have to determine the overall quality of evidence across all the critical outcomes essential to a recommendation they make. Guideline panels usually provide a single grade of quality of evidence for every recommendation, but the strength of a recommendation usually depends on evidence regarding not just one, but a number of patient-important outcomes and on the quality of evidence for each of these outcomes.

When determining the overall quality of evidence across outcomes:

- Consider only those outcomes that are deemed critical;

- If the quality of evidence differs across critical outcomes and outcomes point in different directions — towards benefit and towards harm — the lowest quality of evidence for any of the critical outcomes determines the overall quality of evidence;

- All outcomes point in the same direction — towards either benefit or harm — the highest quality of evidence for a critical outcome that by itself would suffice to recommend an intervention determines the overall quality of evidence. However, if the balance of the benefits and downsides is uncertain, then the grade of the critical outcome with the lowest quality grading should be assigned.

5.1.3. GRADE and meta-analysis

GRADE relies on the judgment about our confidence in a (beneficial or adverse) effect of an intervention and therefore it is impossible to apply GRADE correctly if a meta-analysis is not at least considered and the necessary judgments are made on (statistical, methodological and clinical) heterogeneity. It is possible that no pooled effect can or should be calculated if there is evidence of heterogeneity, be it clinical, methodological or merely statistical, but meta-analysis should always be attempted. Otherwise, it is impossible to gather sufficient elements to make the necessary GRADE judgments. Note that heterogeneity is in most cases a reason to downgrade the body of evidence, with some exceptions that will be explained later.

In order to apply GRADE (but actually in order to make a sound judgment on evidence in general) it is essential that at least one person implicated in the development of the guideline understands this guidance and is able to apply it.

GRADE remains rather vague about what to do if only one study is available. We recommend to downgrade the evidence with at least one level, except when the single study is a multicentre study where sample size in the individual centres is sufficient to demonstrate heterogeneity if there is any. Any decision not to downgrade must be explained and justified.

If the primary studies do not allow the calculation of a confidence interval, consider downgrading as judging precision and heterogeneitiy becomes difficult. There are some rare exceptions, when the confidence interval is not needed as all studies point clearly in the same direction. In some cases non-parametric tests are used because the assumption of normality is violated. In these case, the non-parametric measure of uncertainty should be used (most of the time an interquartile range) and interpreted. Decisions taken around these issues should be justified.